“이번 달 커피값은 5만 원까지만!” 우리 모두 머릿속에 보이지 않는 가계부를 쓰고 있습니다. 흥미로운 건, 이 심적 회계가 같은 돈도 ‘통장 개수’, ‘출처’, ‘라벨’에 따라 전혀 다르게 느끼게 만든다는 사실! 갑자기 생긴 돈은 쉽게 쓰고, 나눠둔 돈은 아까워하고, 여러 개의 작은 할인이 더 매력적으로 보이는 이유.. 모두 이 심리 덕분입니다. 일상의 소비 습관을 조용히 움직이는 보이지 않는 회계 시스템, 심적 회계의 비밀을 함께 알아봅니다.

키워드

#가계부 #마케팅 #소비 #소비습관 #심적회계 #저축

우리는 일상에서 끊임없이 돈을 분류하고 예산을 세웁니다. 실제 가계부에 적지는 않아도 머릿속으로는 이미 각 항목과 예산을 정해 두고 그에 맞추어 쓰고 있죠. 행동경제학에서는 머릿속 가계부를 작성하고 따르는 것을 ‘심적 회계(mental accounting)’라고 부릅니다.

머릿속에서 벌어지는 회계 게임

심적 회계란 사람들이 돈을 물리적으로는 하나의 덩어리로 보면서도, 심리적으로는 서로 다른 ‘계정(account)’으로 분류해서 관리하는 현상입니다. 마치 은행 통장을 여러 개 만들어 용도별로 관리하는 것처럼 사람들은 돈을 식비, 교통비, 학원비, 저축 등의 계정으로 나누어 생각합니다.

이 ‘머릿속 가계부’는 실제 가계부와 달리 매우 유연합니다. 즉, 계정을 마음대로 만들거나 없애고 바꿀 수 있습니다. “이번 달 옷 살 돈이 부족하네? 그럼, 외식비에서 좀 빼자”와 같은 식으로 계정을 조정합니다. 이런 유연성 때문에 때로는 과다 지출을, 때로는 과소 지출을 하게 됩니다.

계정을 깨는 것의 심리적 비용

흥미로운 점은, 사람들은 필요에 따라 계정을 옮겨 쓰면서도 동시에 한 번 만든 심리적 계정을 깨는 데 심리적 저항감을 느낀다는 것입니다. 예를 들어 ‘여행적금’이라 마음먹고 모은 돈을 갑자기 생활비로 써야 할 때, 많은 사람들은 왠지 모를 찜찜함을 느끼곤 합니다. 물리적으로는 같은 돈이지만, 용도가 달라지면 마음의 부담이 생기는 거죠. 이는 우리가 돈에 ‘라벨’을 붙여 관리하기 때문입니다. 각 계정에는 고유한 목적과 의미가 부여되기 때문에 이를 위반하면 불편함을 느끼게 됩니다.

심적 회계를 활용한 현명한 저축법

이런 심리적 특성을 잘 이용하면 돈을 덜 쓰고 저축을 더 많이 할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어 100만 원이 생겼다고 생각해 볼게요. 이 돈을 덜 쓰려면 하나의 큰 통장에 돈을 모두 넣기보다는 여러 개의 통장에 돈을 나누어 넣어 두는 것이 효과적입니다. 100만 원짜리 통장 하나보다는 20만 원, 30만 원, 50만 원짜리 세 개로 나누어 넣어 두는 거죠.

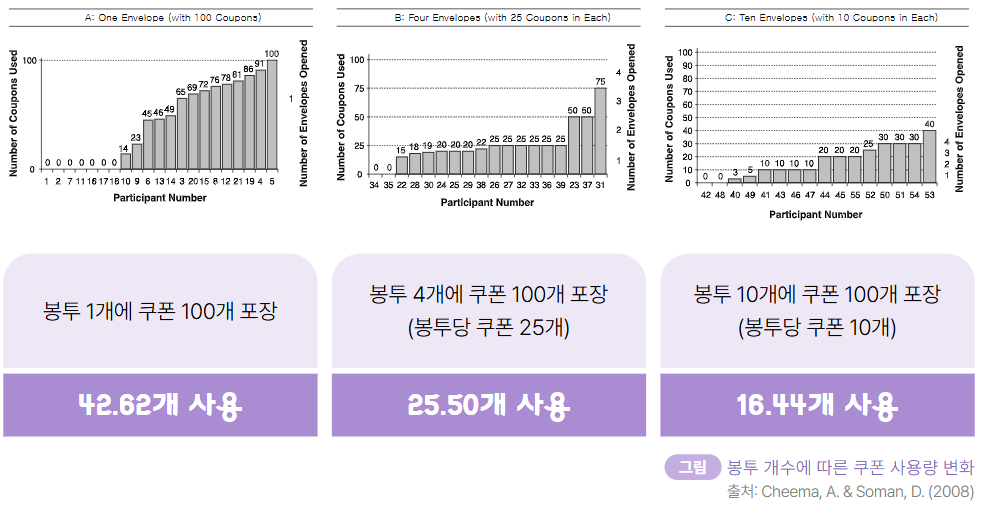

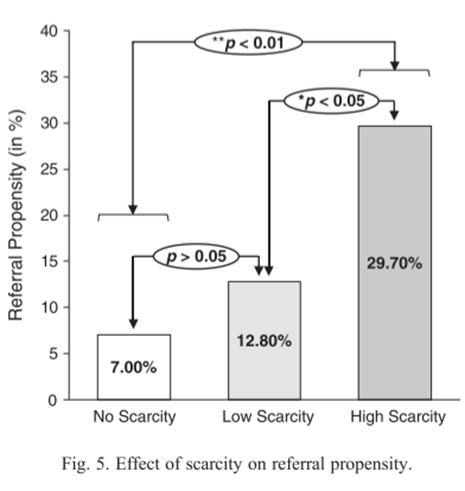

이처럼 돈을 나누어 관리하는 방식이 실제로 소비를 줄이는 데 효과가 있다는 점은 실험으로도 확인된 바 있습니다. 심적 회계의 강력함을 보여주는 유명한 실험을 소개해 드리겠습니다. 캐나다 토론토의 연구자들은 실험 참가자들에게 100개의 쿠폰을 세 가지 방식으로 나누어 준 뒤, 이들이 쿠폰을 얼마나 썼는지 조사했습니다. 첫 번째 그룹에는 100개 쿠폰을 하나의 큰 봉투에 넣어 주었습니다. 두 번째 그룹에는 25개씩 4개의 봉투에 나누어 주었고, 세 번째 그룹에는 10개씩 10개의 봉투에 나누어 주었죠. 결과는 어땠을까요? 같은 100개 쿠폰임에도 불구하고, 봉투가 많을수록 쿠폰 사용량이 적었습니다. 하나의 큰 봉투에 쿠폰을 받은 그룹은 평균 42.62개를 사용했지만, 10개의 봉투에 쿠폰을 나누어 받은 그룹은 16.44개만 사용했죠.

왜 이런 결과가 나왔을까요? 이는 사람들이 각각의 봉투를 별개의 계정으로 인식하고, 그 봉투를 깨는 것에 심리적 저항감을 느끼기 때문입니다. 사람들은 계정을 만들면 계정을 최대한 유지하고 싶어 합니다. 그런데 계정이 깨져버리면 “에라 모르겠다. 그냥 쓰자”라는 생각이 듭니다. 그래서 100개 쿠폰이 들어간 봉투 1개가 깨지면 한 번에 와르르 써버리지만, 쿠폰이 들어간 봉투가 여러 개 있을 때는 보통 한두 개의 봉투만 열어서 씁니다. 따라서 봉투의 개수가 많을수록 더 많은 심리적 장벽이 생긴다고 할 수 있습니다.

돈에 붙이는 심리적 꼬리표

심적 회계에서 또 하나 흥미로운 점은 같은 돈이라도 그 ‘출처’에 따라 쓰는 방식이 달라진다는 점입니다. 직장에 취직해서 받은 첫 월급은 부모님께 드리거나 기념이 될 만한 물건을 사는 경우가 많습니다. 사람들이 첫 월급에 특별한 의미를 부여하기 때문이죠. 또한 내가 일해서 번 특별한 돈이라는 의미 때문에, 그 돈을 함부로 쓰면 심리적 고통이 생깁니다.

반대로, windfall gains라고 불리는 돈이 있습니다. 말 그대로 ‘뜻밖에 얻은 돈’을 뜻하는데요. 연말정산 환급금이나 예상치 못하게 생긴 돈이 여기에 해당합니다. 사람들이 이런 돈을 상대적으로 쉽게 쓰는 이유는 이 돈에 ‘공짜로 생긴 돈’이라는 심리적 꼬리표가 붙기 때문이죠. 그래서 사람들은 이런 돈으로 복권을 사거나 평소보다 비싼 물건을 구매하는 데 주저함이 없습니다.

마케팅에서도 활용되는 심적 회계

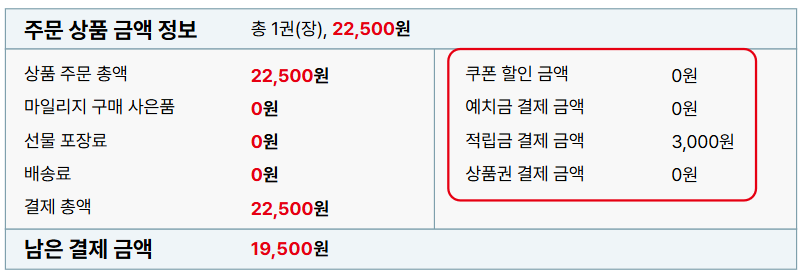

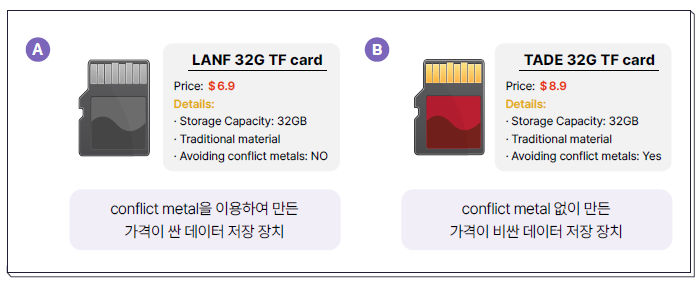

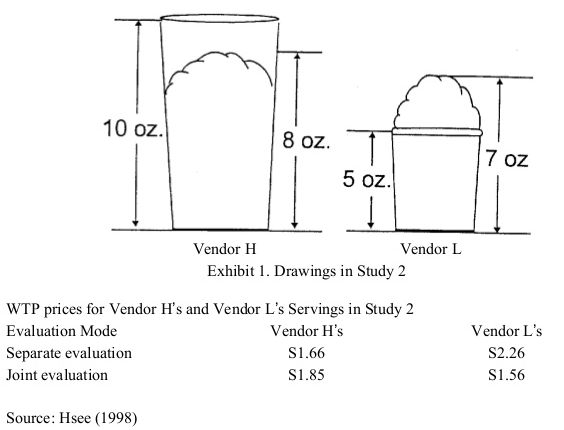

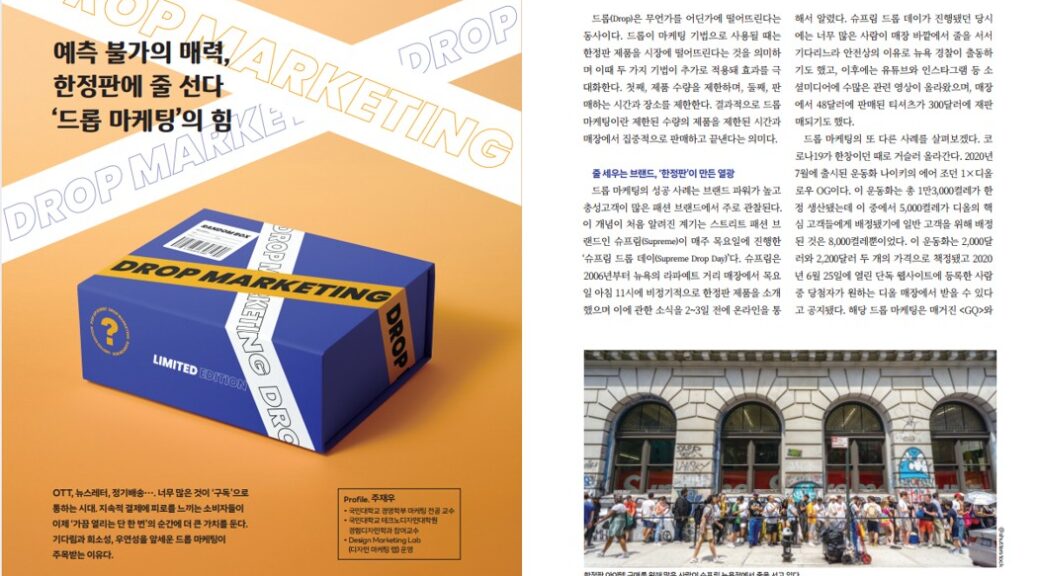

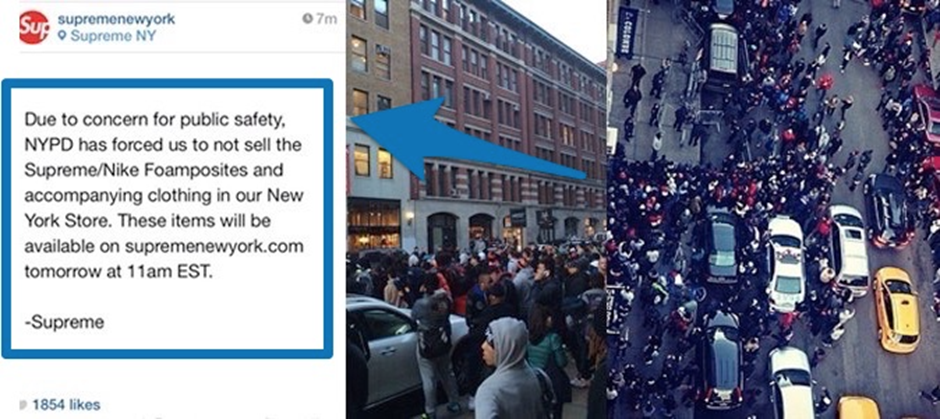

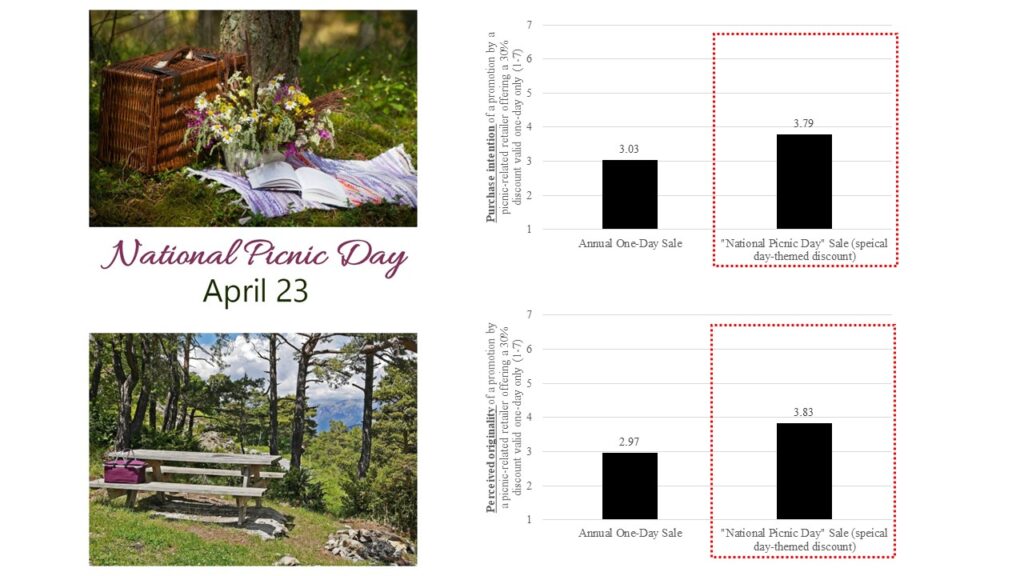

심적 회계는 개인의 소비뿐만 아니라 기업의 마케팅 전략에도 매우 널리 활용되고 있습니다. 우리가 온라인 쇼핑을 할 때 자주 보는 할인 표시를 생각해 봅시다. “3% 할인쿠폰” 하나보다는 “회원 등급 할인 1% + 보유 쿠폰 할인 1% + 적립금 선할인 1%”로 나누어 표시하는 경우가 많습니다. 결과적으로는 같은 3% 할인이지만, 여러 개의 혜택을 받는다는 느낌을 주기 때문이죠. 왜 이런 방법이 효과적일까요? 소비자들이 각각의 할인을 별개의 계정에 들어온 각각의 이득으로 인식하기 때문이에요. 하나의 큰 할인보다는 여러 개의 작은 할인이 더 매력적으로 느껴지죠.

이런 방법을 이용해서 기업은 비싼 제품을 합리화하는 심리적 기법을 사용하기도 합니다. 예를 들어, 비싼 옷이나 전자 기기를 살 때 우리는 종종 망설이는데, 이때 기업들은 제품이 사용될 수 있는 다양한 상황을 제시해서 소비자의 심적 계정을 여러 개로 나누도록 유도합니다. 예를 들어 20만 원짜리 블라우스가 비싸게 느껴질 때, 판매자는 이렇게 제안합니다. “월요일은 원피스 안에 겹쳐 입고, 화요일은 재킷 안에 받쳐 입고, 수요일은 맨투맨 위에 포인트로 활용하세요.” 하나의 옷을 여러 가지 용도로 나누어 생각하게 만들죠. 그러면 소비자는 무의식적으로 상황별 가성비를 계산합니다. ‘직장용으로 3만 원, 데이트용으로 3만 원, 캐주얼용으로 3만 원, …’ 이런 식으로 말이에요. 같은 20만 원이지만 심리적으로는 훨씬 합리적인 구매로 느껴지는 것이죠.

심적 회계와 현명한 동행

소비자 입장에서는 심적 회계와 같은 심리적 메커니즘을 이해하고 현명하게 대응해야 합니다. 예를 들어, “이 할인들이 정말 별개의 혜택일까?”, “이 제품을 정말 이렇게 많은 용도로 사용할까?” 같은 질문을 던져야 해요.

또한 최근에는 모바일 결제, 가상화폐, 주식 등 물리적 형태가 없는 돈이 늘어나고 있습니다. 이러한 돈은 추상적이라 심리적 고통을 덜 주기 때문에 훨씬 쉽게 쓰입니다. 현금을 직접 건네주는 것과 카드를 긁는 것, 디지털 결제 사이에는 분명한 심리적 차이가 존재하죠. 이런 함정에 빠지지 않으려면 디지털 결제 후에도 영수증을 확인하는 습관을 들여야 합니다. 항목과 금액을 다시 한번 확인하면서 ‘진짜 돈을 썼다’라는 실감을 되찾을 필요가 있습니다.

결국 심적 회계는 양날의 칼입니다. 잘 활용하면 절약의 도구가 되지만, 방심하면 비합리적 소비의 원인이 되죠. 다음번에 “이번 달 커피값은 5만 원까지만”이라고 다짐할 때, 그것이 단순한 예산 관리가 아니라 정교한 심리 게임의 일부라는 것을 기억하시길 바랍니다. 우리가 머릿속에서 돈을 어떻게 분류하고 관리하는지 이해할수록, 모은 돈은 더 아끼고 필요할 때는 더 잘 쓰는 현명한 소비자가 될 수 있

***

Reference

Cheema, A. & Soman, D. (2008). The Effect of Partitions on Controlling Consumption. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 665-678.

The authors demonstrate that partitioning an aggregate quantity of a resource (e.g., food, money) into smaller units reduces the consumed quantity or the rate of consumption of that resource. Partitions draw attention to the consumption decision by introducing a small transaction cost; that is, they provide more decision-making opportunities so that prudent consumers can control consumption. Thus, people are better able to constrain consumption when resources associated with a desirable activity (which they are trying to control) are partitioned rather than when they are aggregated. This effect of partitioning is demonstrated for the consumption of chocolates (Study 1) and gambles (Study 2). In Study 3, process measures reveal that partitioning increases recall accuracy and decision times. Importantly, the effect of partitioning diminishes when consumers are not trying to regulate consumption (Studies 1 and 3). Finally, Study 4 explores how habituation may decrease the amount of attention that partitions draw to consumption. In this context, partitions control consumption to a greater extent when the nature of partitions changes frequently.